January 17 - March 30, 2019

We Need to Talk About Paintings

-

Laurette Atrux-Tallau, Aïda Kazarian, Nicolas Floc'h, Pierre Gerard

Laurette Atrux-Tallau, Aïda Kazarian, Nicolas Floc'h, Pierre Gerard -

Exhibition view

Exhibition view -

Yoann Van Parys, Laurette Atrux-Tallau, Aïda Kazarian

Yoann Van Parys, Laurette Atrux-Tallau, Aïda Kazarian -

Adrien Lucca, "SCW-30 version 1", SCW-30 version 1, 2019, Luminaire LED fluorescent, polycarbonate peint 51 x 16,5 x 4,3 cm Edition de 5 ex + 1 AP © Adrien Lucca

Adrien Lucca, "SCW-30 version 1", SCW-30 version 1, 2019, Luminaire LED fluorescent, polycarbonate peint 51 x 16,5 x 4,3 cm Edition de 5 ex + 1 AP © Adrien Lucca -

Yoann Van Parys "Gebel Grin", 2018 acrylique et encre de sérigraphie sur verre, aluminium (17,9 x 27,5 cm) + (42 cm de diamètre) sur 60 x 5 x 2,5 cm Pièce unique.

Yoann Van Parys "Gebel Grin", 2018 acrylique et encre de sérigraphie sur verre, aluminium (17,9 x 27,5 cm) + (42 cm de diamètre) sur 60 x 5 x 2,5 cm Pièce unique. -

Nicolas Floc'h, série "Colonne d'eau", 2015, tirage pigmentaire sur papier mat Fine Art, 57,5 x 41,5 cm Edition de 5 ex + 1 AP Pierre Gerard, "Couple flottant, 2019, Peinture à l'huile sur carton 71 x 79,5 cm Pièce unique.

Nicolas Floc'h, série "Colonne d'eau", 2015, tirage pigmentaire sur papier mat Fine Art, 57,5 x 41,5 cm Edition de 5 ex + 1 AP Pierre Gerard, "Couple flottant, 2019, Peinture à l'huile sur carton 71 x 79,5 cm Pièce unique. -

Couple flottant, 2019 Peinture à l'huile sur carton 71 x 79,5 cm Pièce unique

Couple flottant, 2019 Peinture à l'huile sur carton 71 x 79,5 cm Pièce unique -

Pep Vidal "Rolling Painting",2018 Acrylique sur papier 212 x 25 cm Pièce unique

Pep Vidal "Rolling Painting",2018 Acrylique sur papier 212 x 25 cm Pièce unique -

Exhibition view

Exhibition view -

Exhibition view

Exhibition view -

Lionel Estève, "sans titre", 37 galets et aquarelle, pièce unique

Lionel Estève, "sans titre", 37 galets et aquarelle, pièce unique

Group Show

We need to talk about Paintings

‘We need to talk about paintings’ is our second collective exhibition. Since the creation of our gallery in September 2016, painting has been the least represented medium on our walls. That is why we felt the desire to express our interest in painting, albeit in our own way. Not necessarily in a direct, more often in an allusive manner. Hence our mock-solemn title. We decided to invite artists whose practice seems to us to evinceanenlarged eldofpaintingortoquestionthatpractice.

Laurette Atrux-Tallau (1969) appropriates illustrations which she nds in natural science magazines from the 1960’s/1970’s, on which she applies drops of nail varnish which saturate or create geometrical shapes. On other images she repeats motifs which disturb the legibility of subjects or she emphasises certain elements. We oscillate between an atmosphere of German Romantic painting and an almost Pop-like exaggeration.

The work by Detanico & Lain (1974 / 1973) is part of the ’27 rue de Fleurus’ series, a homage to Gertrude Stein’s Paris address. The Brazilian duo has created a font named ‘Cubica’ and inspired by Cubism. They have translated one of her poems into In this new font. Like the format the colours come straight out of a painting that used to belong to Gertrude Stein, who was also a patron of the arts. You can recognise here Picasso’s palette of blues and pinks as he painted an acrobat clad in blue walking about on a ball, as a massive man in pink and blue looks at him.

Nicolas Floc’h (1970) is proposing two complementary objects. One sound piece entitled ‘The colour of water’, the result of a meeting with Hubert Loisel, a researcher at the Oceanology and Geosciences Laboratory, at the CNRS, at ULCO and at Lille University, and on the other hand three monochromes. These are underwater photographs of columns of water which envelop us like an entity of colour. The project aims to collect monochromes as a way to reproduce all existing nuances of water and making it possible to understand the adaptation of phytoplankton linked to its photosynthetic activity.

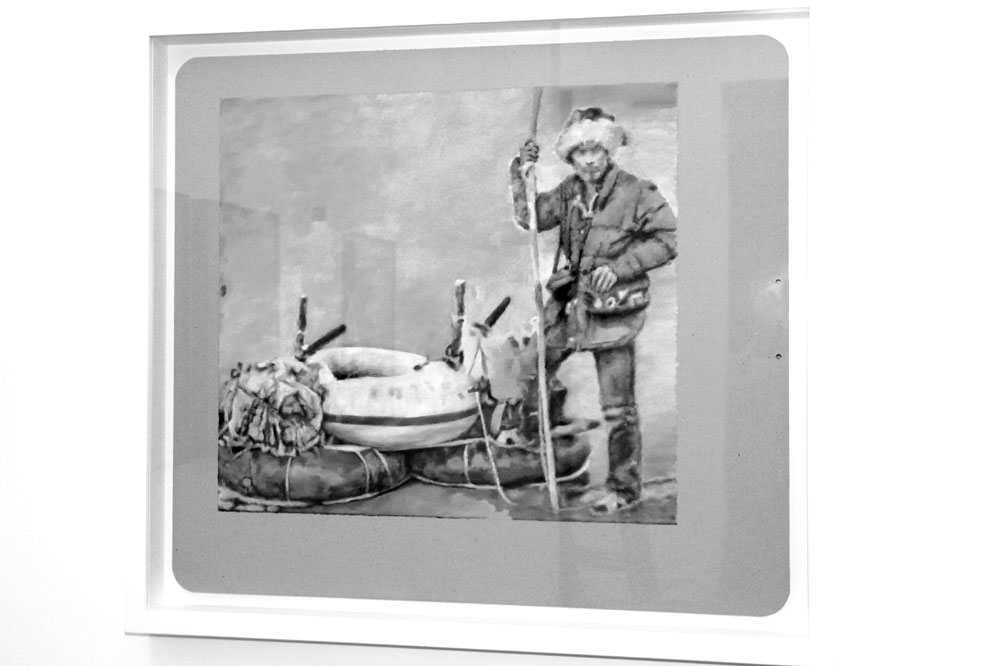

Pierre Gerard (1966) ‘Floating Couple’ is an oil painting on fruit cardboard of an appropriation, that of a pre-existing image, illustrating the ingenuity of man. Starting from a number of disparate elements, the main character here creates a precarious boat. For the rst time in the artist’s painted work the image is shifted so as to underline the dimension of the lack. For those who know Pierre Gerard’s sculptures, there is a meaningful hint involved, as he assembles disparate fragments to nally give birth to mysterious sculptures.

In this large-scale work Aïda Kazarian (1952) tirelessly repeats the ngerprint of her index. She applies paint in a boustrophedon manner that is typical of the work of Caucasus rugs, re ecting the intermixing of cultures in that region. This refers directly to her Armenian family roots. She questions the support with this semi-transparent navy canvas which partly reveals the structure of the frame. The slightly pearlescent colour reacts delicately to the light and the variety of the traces generates a feel of soft vibration.

Adrien Lucca (1983) has been working for many years on light and colour. Here he is proposing an extension of the experiments presented last year in his personal show as well as those that led to making the permanent installation in the Rotterdam metro inaugurated in December 2018.

Yoann Van Parijs (1981) collects and assembles. He superimposes and apposes. He captures what strikes him in the urban space, both through photographs and through sketches. He gathers fragments from building sites, on which he applies his layers of paint which scramble or illuminate his vision of the world. And so he oscillates between abstraction and guration, between reality and energy.

Pep Vidal (1980) is presenting ‘Tree’: at the origin of this painting/sculpture there is the discovery, on a pavement in Amsterdam, of a small r tree. Then came the insane desire to go and plant it back in Sweden, in a kind of expedition to return to the origins. Then, as often with Pep Vidal, came the question of the volume of that tree. He was to use the method called ‘rolling painting’. The quantity of water you could put in the cylinder corresponds to the volume of the tree and the quantity of paint used would make it possible to cover the whole of it.

Lionel Estève (1967) invites us to contemplate some stones which seem to have gorged themselves in contact with a coloured brook. Some of them are equipped with dividing lines between air and water, while other ones are entirely submerged. The watercolour caresses the stone and addresses a notion that is dear to the artist: that of producing a painting which questions sculpture.